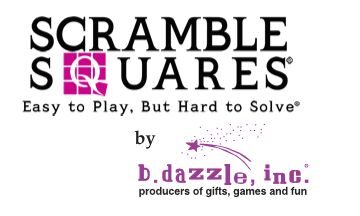

Description

The rugged great outdoors, enjoyed, protected and pursued, is the theme of this rock climbing, white water rafting, hiking, camping ‘Wilderness Adventure’ Scramble Squares® puzzle.

Fascinating Facts

Millions of people head for the great outdoors every year to participate in hiking, camping, kayaking, rock climbing, whitewater rafting and other wilderness adventures for the exhilaration of the activity itself, but even more for the therapeutic and rejuvenating effect of communing with unspoiled nature. The complexities and stresses of modern life evaporate in the peacefulness and simplicity of beautiful views, rich flora, the sounds of rustling leaves, babbling water and singing birds, and an occasional surprise visit by wildlife– a squirrel, a chipmunk, a deer or other seldom encountered fellow inhabitants of Mother Earth. There are avid hikers of all backgrounds and ages, from weekend hikers who hike 5 to 20 miles to the most adventurous backpackers who participate in expeditions of 1,000 to 2,000 miles. Intrepid survivalists and average citizens, ages 14 to 80, hike to appreciate hiking’s unique personal rewards, from the special solitude and the eerie beauty of a southwestern desert hike down to the floor of the Grand Canyon to a vigorous and brisk climb up a wind-whipped Alpine slope.

Rock climbing is one of the fastest growing adventure sports. Strategy, strength, endurance and problem-solving are among the basic skills needed to surmount the challenge of a sheer rock face and reach the height of one’s own ability. Beginning rock climbers often utilize the “top-rope” approach. In top-roping, an anchor point at the top of the rock surface to be climbed serves as an overhead pulley, and the climber’s rope runs from the climber’s partner on the ground, who stabilizes the climber by holding one end of the climbing rope (the “belayer”), through an alloy “carabiner” attached to the anchor point at the top (a sturdy, deep-rooted tree, or a schism in solid rock) and back down to attach to the climber. As the climber works his/her way up the rock face, the belayer prevents slack in the rope by pulling on the rope with one hand and guiding it through the “belay brake” with the other hand. When the climber reaches the top of his climb, he is lowered back down to the ground as the belayer gradually lets out the rope.

The canoe is one of the oldest forms of transportation, second only to the raft. Canoes dug out of logs were being manufactured at least 8,000 years ago, but light, maneuverable canoes were developed much later in North America by covering a frame with animal skins, fabric, or bark. The birch bark canoe used by Native Americans was adopted by French explorers and fur traders during the 17th Century. The Eskimo kayak, which has a partly enclosed deck with openings for the paddlers’ seats, was later discovered by European explorers. The canoeist uses a single bladed paddle that is similar to the oar used in rowing, but the kayak paddle has a blade on each end and is gripped in the middle. John MacGregor, a Scottish lawyer was named largely responsible for the popularity of canoeing as a recreational sport. In 1845, he designed a type of canoe, the Rob Roy, which had a deck and was equipped with a mast and sail, as well as paddles. MacGregor went on a series of cruises in Europe and in the Holy Land, beginning in 1849, and he wrote books and delivered many lectures about his trips. Canoeing became a full-fledged Olympic event in 1936.

Whitewater river rafting provides the average person with the adrenalin rush usually reserved for participants in extreme sports and the unexpected, breathtaking natural beauty experienced only by explorers. River runners experience the anxious anticipation of what awaits around the river’s bend as well as the tranquility of floating on flat water through canyons and gorges that shut out the direct sunlight passing diverse vegetation growing along sunny river banks. Suddenly, the tranquility of the river is bombarded by the deafening roar of unseen wild white water rapids that will test both the strength and the courage of rafters until they are once again gliding peacefully on flat water. The rafters stabilize themselves in the raft by jamming their feet into the gaps between the inflatable raft’s wall and floor, leaning forward as far as possible and planting their paddles again and again into the water, like ski poles during a slalom run. They lean on the water with their paddles, but the water is moving faster than their paddles, and the raft collides with a wall of water, drenching the rafters! The rubber raft bounces over the great white wave that it had just smashed into. As the water washes over the raft, the rafters count heads to see if anyone is missing. When a rafter is dumped into the river, he/she rides the river on his/her life jacket until picked up by the rafters in a following raft! The International Scale of River Difficulty classifies rapids on a scale of I to VI with Class I being easy and Class VI being unrunnable. For guided whitewater rafting, Class III is considered the beginning level.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.